The man behind Tiger’s first deals breaks his silence with a new autobiography

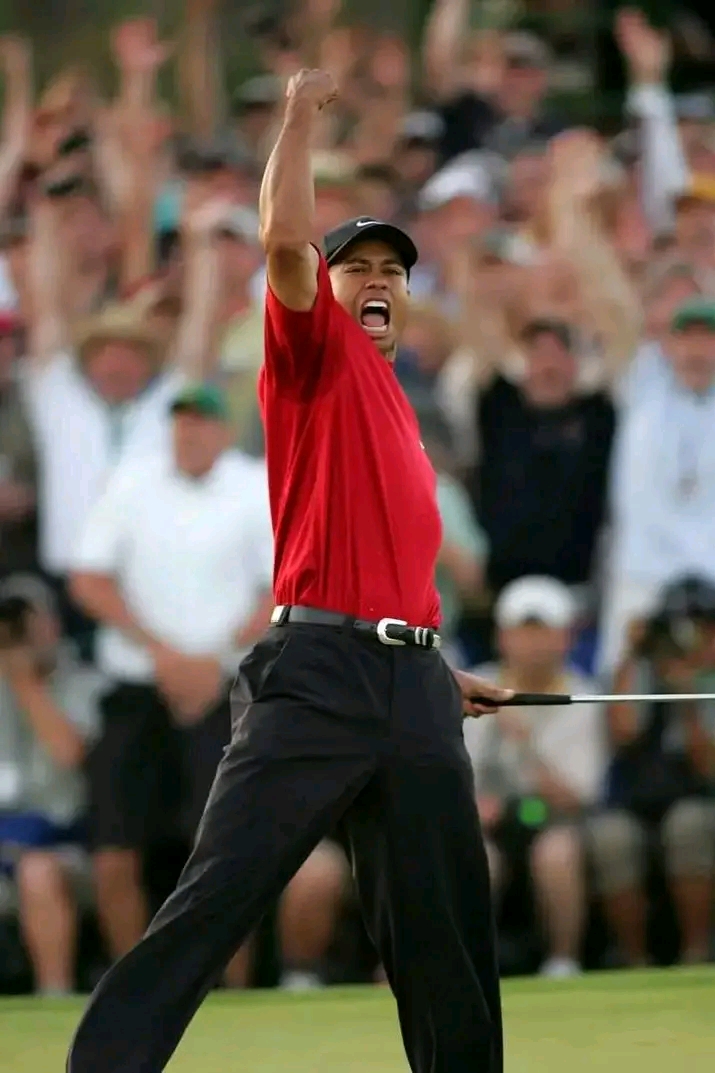

It is no exaggeration to say that Hughes Norton operated at the epicenter of professional golf for nearly 20 years, helping legendary super-agent Mark McCormack grow the personal-management business McCormack created that at its height called the majority of the top 25 players in the world clients. While at IMG, Norton represented Greg Norman when the Australian World No. 1 was at the peak of his powers and built a relationship with Earl Woods that resulted in the highest-profile new-professional-golfer-representation agreement of all time. Norton also led the negotiations that would make Tiger Woods the highest-earning active golfer on the planet before he hit his first shot for pay at the 1996 Greater Milwaukee Open. In this excerpt from his memoir, Rainmaker, out for sale March 26, Norton offers the first glimpse inside the negotiations and machinations that launched Woods’ branding juggernaut—with dollar signs attached that still stick out even in a world of LIV Golf mega-deals.

I can’t recall the precise moment when I heard from Earl or Tiger that the decision had been made [to turn professional], but it was well before U.S. Amateur No. 3 because that week [in 1996] at Pumpkin Ridge Golf Club, I had with me a couple of very big contracts for Tiger to sign, the fruit of several weeks of “what-if ” negotiations with Nike and Titleist. By the time Tiger raised the trophy that Sunday evening in Portland, Ore., his Nike logo apparel had been sized and tailored, his Nike shoes had been tested for comfort and a Titleist staff bag emblazoned with his name and filled with a set of custom-fitted clubs was as ready to hit the PGA Tour as he was.

The process had begun two years earlier, just after Tiger won his first Amateur. (I was not officially his agent—I couldn’t be until the day he publicly renounced his amateur status—but we had a tacit understanding.) My strategy was a bit unorthodox: Instead of stirring interest among several apparel and equipment companies in the hope of creating a bidding war, I decided to put all my eggs in two baskets—Nike and Titleist. It was a gamble, to be sure, but one I thought could pay off.

Nike, I suspected, would require more spadework than Titleist, so it was there that I commenced. Thanks once again to the unique resources of IMG, I had a couple of things going for me. A few years earlier our tennis division had established a strong relationship with Nike, bringing them the flamboyant Andre Agassi, who had been the perfect fit for Nike’s studiedly edgy image.

TEAM TIGER From left: IMG executive Clarke Jones, Woods and Norton in 1996. Photograph courtesy of the Norton Family Archive

Nike’s director of sports marketing, Steve Miller, was the former athletic director at Kansas State University, where he had transformed a losing football team into a perennial bowl invitee by hiring Hall of Fame coach Bill Snyder. Steve would be my interlocutor in negotiating the Tiger deal.

After three or four visits with Miller, I felt my homework was completed, and I was ready to talk Tiger. Here was my thinking:

(1) The explosive growth of golf had not gone unnoticed by Nike. The company had made a tentative first move into the game with shoes and apparel and was on the cusp of a bigger commitment into clubs and balls.

(2) Nike prided itself on identifying with only the very best players in their respective sports—Andre Agassi, Michael Jordan, Jerry Rice. Stars drove the Nike brand.

(3) Those guys now were past their primes, aging out of the picture. Nike had not signed a megastar in years. They needed a win.

(4) Tiger would give it to them. The timing was perfect.

(5) Phil Knight was a jock sniffer who simply had to sign the best athletes. If he was already paying Agassi and Jim Courier big bucks, I reasoned, imagine what he might pay the best young golfer to come along since Jack Nicklaus.

With that in mind, I put my cards on the table: “Here’s a generational talent with charisma and global appeal who will instantly rocket Nike Golf into the big leagues. Not only are we coming to you first and exclusively, but we will give you the opportunity to own Tiger’s identity. The Nike swoosh on his shirt front and cap will be the only branding he displays—no other company logos on the shirt collar, chest, sleeves or back of the hat—a pure Nike message, front and center, for all to see. Based on his unprecedented amateur achievements, every other company will want him. Nike can preempt them all, but it’s going to cost top dollar.”

Then, swallowing hard, I told Steve about $50 million over five years would get it done. No one else in golf—not Palmer, not Norman, no one—was earning anything like that for apparel and shoes, but through our tennis guys, I knew Agassi’s Nike contract was about $5 million a year, and from Steve I had a pretty good feel for Jordan’s compensation, so I thought, Why not go for it?

Steve’s first response, of course, was “That’s ridiculous,” but he didn’t say forget it. From the beginning he was straightforward about Nike’s strong interest. I figured the $50 million, while an overreach, wasn’t too far from where I might be able to end up, and that was a huge win not simply in sheer dollars but in the worldwide promotional power Nike would bring to the table. No other company in golf had the advertising budget or clout to help make Tiger a household name. On that score, Nike could have argued that it should pay Tiger less, not more. But they never did.